Shadow Play and Geometry: The Optical Phenomena of Hard Edge Painting

By Andrew Bay, UK

Countless attempts have been made to define once and for all, what Abstract Art might be. Although no final consensus on this definition will arguably ever be reached, we can more or less accept that, Abstract Art, is art, that does not set out to produce an explicit depiction of visual reality, but instead uses the raw materials of shapes, colours, forms and gestural details, to achieve its effects. Among the manifold schools of Abstract Art which flourished during the course of the XX century, Hard Edge in particular, comes to mind for the unsung heroes and groundbreaking pioneers it has produced.

There are great similarities between Hard Edge and Minimalism, and they are often referred to interchangeably. Indeed, they are certainly not mutually exclusive, and they do share a great deal of similar concepts and aesthetic principles. But let us backtrack a few decades prior to the beginning of the Hard Edge movement, to briefly consider Geometric Abstraction. This movement, which was a true forerunner of modernity, started just aft the turn of the XX century, around the time of the Great War. The doctrines of Geometric Abstraction mainly consisted in the study of unadorned geometric forms, in non-illusionistic spaces. In other words, the focus of Geometric Abstraction was exclusively aimed at 2 dimensional objects: there was no concern for 3 dimensional space or practical reality: Geometric Abstraction was, for the most part, entirely non-objective. Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian were the two most famous exponents of this tradition. They were both fully intent on discovering that plane of reality which, they assumed, must exist beyond this messy world of tangible things and objects we live in. And this is the core principle which defines the Hard Edge school of painting: an attempt to abstract meaning and design, from the work of art.

Hard Edge artists used sharp, clear edges and unexpected transitions in their paintings, with large spaces enclosed in flat colours. Their primary concern was with the economy of forms in predominantly geometric shapes, the roundness of colours, which may become bright and saturated, the absence of personality in the execution. Hard Edge artists were united in their refusal to commit to the idea of authorship for their work: in a sense they were very "anti-painterly." Across even surface planes, Hard Edge painters designed structures, and often entire systems, to establish how their paintings can be created. Historically, two schools, on both American coasts, heralded this new aesthetic. The Californian West Coast Hard Edge painters were the Four Abstract Classicists: Karl Benjamin, John McLaughlin, Frederick Hammersley and Lorser Feitelson; on the East Coast in New York, the key players were Josef Albers, Ellsworth Kelly and Kenneth Noland.

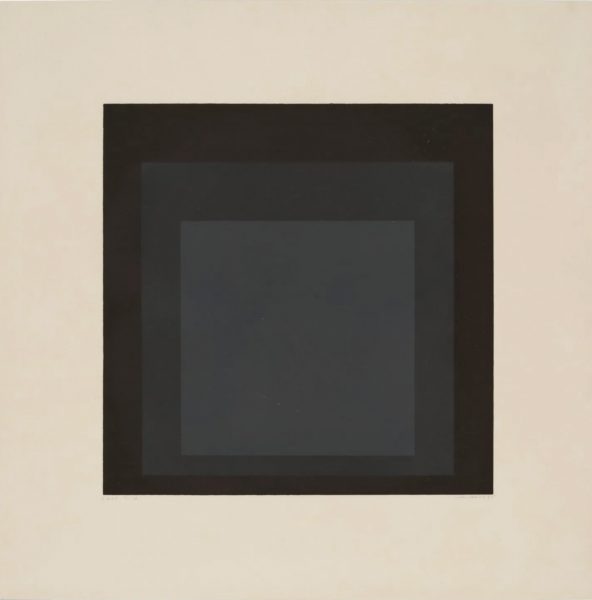

Josef Albers was born in Germany in 1888 in a family of handymen and blacksmith. He was trained as a printmaker and stained-glass maker in Essen from 1916 to 1919. In 1920 he enrolled at the prestigious Bauhaus Art School in Weimar, where he eventually became a professor of furniture design in 1925. His colleagues at Bauhaus were soon-to-be world-famous artists such as Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky. In 1933, Albers moved to the US to escape the rise of Nazism in Germany. He was offered a position at the liberal arts Black Mountain College in North Carolina, where he counted Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly as his students. His most famous work is his "Homage to the Square" series, which is a textbook Hard Edge composition. The "Homage" essentially is a superimposition of 4, 18 inches x 18 inches squares, which he painted over and over through the years. On the paintings, 4 different planes of colour systematically overlap each other, in typical Hard Edge fashion. Albers famously said: "In the end, the study of colour is the study of ourselves."

Kenneth Noland was born in 1924 and studied art at Black Mountain College, in North Carolina, his home state, with none other than Joseph Albers himself. Some of his classical Hard Edge works included his "Targets" and "Stripes" series, in which he steadily endeavoured to remove all texture, gesture and emotional content from his paintings.

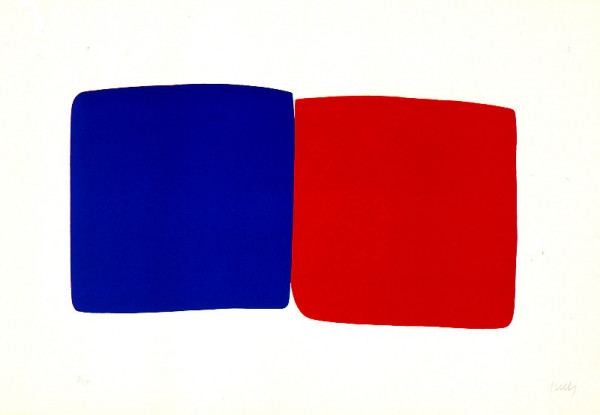

Ellsworth Kelly was born in 1923 in Orange County, New York into a middle-class family and studied art at the School of Fine Arts in Boston and the prestigious Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris. His first notable major works were a series of collages which he designed in 1951 and which were published in a book called "Line Form And Colour." The work was strongly influenced by the Geometric Abstractions of Malevich, with an emphasis on blocks of pure colour and meticulous experimentation with relationships of colours. He gradually discarded formal structures to focus more closely on random associations of separate square canvasses; "Colours For a Large Wall" (1951), for which he designed 64 separate square canvasses, merged into a single unit, is a classic Hard Edge artwork. It embodies the concept of an additive composition, where the artist starts with one pattern and then keeps adding more and more elements to the original design. Ellsworth was deeply interested in producing "non-objective" work, from which the artist could be completely removed. In "Sculpture For a Large Wall" (1957) the random placement of metal and aluminum sheets objects in both negative and positive spaces creates a striking interaction between 3D angles and the reflection of light on the sheets. With his "Red, Yellow, Blue" series (1968) Kelly went a step further, and started to think in terms of creating new shapes for each painting altogether, in the style of his contemporary Frank Stella. He started to experiment with the shape of the canvas, thus transforming them into objects in themselves and divesting them of their art work status.

Karl Benjamin

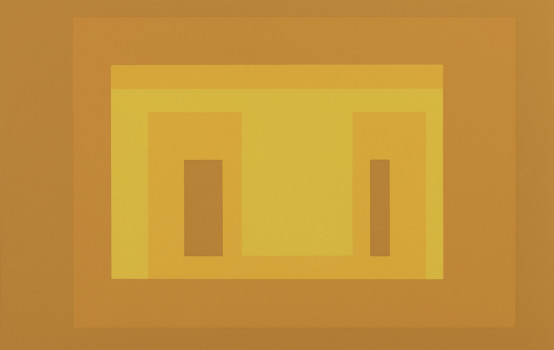

Karl Benjamin was the most important voice of the Hard Edge West Coast movement. An elementary school teacher, who became a self-taught artist in the 1950s he became the unintentional leader of the Californian Abstract Classicists West Coast Hard Edge School. With bright saturated colours, and a predilection for oil paint as opposed to acrylic which he didn’t particularly enjoy using, he developed a classic Hard Edge body of work, centred around the study of trapezoid, tiles-like geometric shapes and patterns. Benjamin and his fellow Hard Edge contemporaries, were essentially reacting against Abstract Expressionism and the Jackson Pollock school of overemphasis on emotional exuberance. The Hard Edge artists rejected an approach to art making, which claimed that "the process was the art." These painters wanted, on the contrary, to remove the process from their art, removing the possibility of choice from their work. The Hard Edge movement was concerned with the actual painting as an object, which could be reflected in the size of the actual canvas, or in the way it was mounted over the wall; their focus was on the exploration of simple geometric shapes, (as demonstrated by Karl Benjamin) and the design of orderly compositional systems. Symbols and messages were barred entry from the creative space, and the work of art was seen purely as self-referential. The artists were employing a minimum amount of devices to produce their works, such as textures, lines, shapes and colour, which purpose had been simplified to being a mere material in the overall picture. Repetition and patterns were the only building blocks required to create an entirely new approach to modern painting.

By Andrew Bay, UK

Countless attempts have been made to define once and for all, what Abstract Art might be. Although no final consensus on this definition will arguably ever be reached, we can more or less accept that, Abstract Art, is art, that does not set out to produce an explicit depiction of visual reality, but instead uses the raw materials of shapes, colours, forms and gestural details, to achieve its effects. Among the manifold schools of Abstract Art which flourished during the course of the XX century, Hard Edge in particular, comes to mind for the unsung heroes and groundbreaking pioneers it has produced.

There are great similarities between Hard Edge and Minimalism, and they are often referred to interchangeably. Indeed, they are certainly not mutually exclusive, and they do share a great deal of similar concepts and aesthetic principles. But let us backtrack a few decades prior to the beginning of the Hard Edge movement, to briefly consider Geometric Abstraction. This movement, which was a true forerunner of modernity, started just aft the turn of the XX century, around the time of the Great War. The doctrines of Geometric Abstraction mainly consisted in the study of unadorned geometric forms, in non-illusionistic spaces. In other words, the focus of Geometric Abstraction was exclusively aimed at 2 dimensional objects: there was no concern for 3 dimensional space or practical reality: Geometric Abstraction was, for the most part, entirely non-objective. Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian were the two most famous exponents of this tradition. They were both fully intent on discovering that plane of reality which, they assumed, must exist beyond this messy world of tangible things and objects we live in. And this is the core principle which defines the Hard Edge school of painting: an attempt to abstract meaning and design, from the work of art.

Hard Edge artists used sharp, clear edges and unexpected transitions in their paintings, with large spaces enclosed in flat colours. Their primary concern was with the economy of forms in predominantly geometric shapes, the roundness of colours, which may become bright and saturated, the absence of personality in the execution. Hard Edge artists were united in their refusal to commit to the idea of authorship for their work: in a sense they were very "anti-painterly." Across even surface planes, Hard Edge painters designed structures, and often entire systems, to establish how their paintings can be created. Historically, two schools, on both American coasts, heralded this new aesthetic. The Californian West Coast Hard Edge painters were the Four Abstract Classicists: Karl Benjamin, John McLaughlin, Frederick Hammersley and Lorser Feitelson; on the East Coast in New York, the key players were Josef Albers, Ellsworth Kelly and Kenneth Noland.

Josef Albers was born in Germany in 1888 in a family of handymen and blacksmith. He was trained as a printmaker and stained-glass maker in Essen from 1916 to 1919. In 1920 he enrolled at the prestigious Bauhaus Art School in Weimar, where he eventually became a professor of furniture design in 1925. His colleagues at Bauhaus were soon-to-be world-famous artists such as Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky. In 1933, Albers moved to the US to escape the rise of Nazism in Germany. He was offered a position at the liberal arts Black Mountain College in North Carolina, where he counted Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly as his students. His most famous work is his "Homage to the Square" series, which is a textbook Hard Edge composition. The "Homage" essentially is a superimposition of 4, 18 inches x 18 inches squares, which he painted over and over through the years. On the paintings, 4 different planes of colour systematically overlap each other, in typical Hard Edge fashion. Albers famously said: "In the end, the study of colour is the study of ourselves."

Kenneth Noland was born in 1924 and studied art at Black Mountain College, in North Carolina, his home state, with none other than Joseph Albers himself. Some of his classical Hard Edge works included his "Targets" and "Stripes" series, in which he steadily endeavoured to remove all texture, gesture and emotional content from his paintings.

Ellsworth Kelly was born in 1923 in Orange County, New York into a middle-class family and studied art at the School of Fine Arts in Boston and the prestigious Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris. His first notable major works were a series of collages which he designed in 1951 and which were published in a book called "Line Form And Colour." The work was strongly influenced by the Geometric Abstractions of Malevich, with an emphasis on blocks of pure colour and meticulous experimentation with relationships of colours. He gradually discarded formal structures to focus more closely on random associations of separate square canvasses; "Colours For a Large Wall" (1951), for which he designed 64 separate square canvasses, merged into a single unit, is a classic Hard Edge artwork. It embodies the concept of an additive composition, where the artist starts with one pattern and then keeps adding more and more elements to the original design. Ellsworth was deeply interested in producing "non-objective" work, from which the artist could be completely removed. In "Sculpture For a Large Wall" (1957) the random placement of metal and aluminum sheets objects in both negative and positive spaces creates a striking interaction between 3D angles and the reflection of light on the sheets. With his "Red, Yellow, Blue" series (1968) Kelly went a step further, and started to think in terms of creating new shapes for each painting altogether, in the style of his contemporary Frank Stella. He started to experiment with the shape of the canvas, thus transforming them into objects in themselves and divesting them of their art work status.

Karl Benjamin

Karl Benjamin was the most important voice of the Hard Edge West Coast movement. An elementary school teacher, who became a self-taught artist in the 1950s he became the unintentional leader of the Californian Abstract Classicists West Coast Hard Edge School. With bright saturated colours, and a predilection for oil paint as opposed to acrylic which he didn’t particularly enjoy using, he developed a classic Hard Edge body of work, centred around the study of trapezoid, tiles-like geometric shapes and patterns. Benjamin and his fellow Hard Edge contemporaries, were essentially reacting against Abstract Expressionism and the Jackson Pollock school of overemphasis on emotional exuberance. The Hard Edge artists rejected an approach to art making, which claimed that "the process was the art." These painters wanted, on the contrary, to remove the process from their art, removing the possibility of choice from their work. The Hard Edge movement was concerned with the actual painting as an object, which could be reflected in the size of the actual canvas, or in the way it was mounted over the wall; their focus was on the exploration of simple geometric shapes, (as demonstrated by Karl Benjamin) and the design of orderly compositional systems. Symbols and messages were barred entry from the creative space, and the work of art was seen purely as self-referential. The artists were employing a minimum amount of devices to produce their works, such as textures, lines, shapes and colour, which purpose had been simplified to being a mere material in the overall picture. Repetition and patterns were the only building blocks required to create an entirely new approach to modern painting.