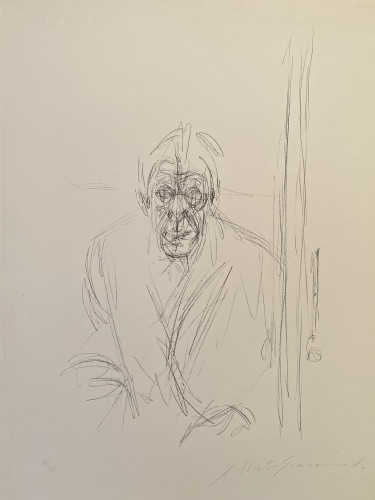

Obsession and Passion: the visionary world of Alberto Giacometti

By Andrew Bay, UK

In the late 1950s, Alberto Giacometti's studio in Paris was a safe heaven for some of the most important artists and writers of the 20th century. Jean Genet, the great novelist and playwright once said: "Giacometti's studio was a magic cauldron out of which he could conjure prodigious art, from a messy dump." Plaster mixed with paint and all sorts of scattered materials, filled the sculptor's apartment's floor, feeding his frenzy of creative outbursts. This chaos would eventually find its way onto a frame which would take a permanent form, great art inevitably grown from scraps and debris.

Giacometti was born in Switzerland in 1901, the son of a well established painter. He developed an interest in sculpture from an early age, and decided to become a painter when he was 14 years old. He enrolled at the Geneva School of Fine Arts as a teenager and eventually relocated to Paris in 1923, to study under Emile Bordelles, a former protege of the great sculptor Auguste Rodin.

In Paris, Giacometti rapidly found himself drawn to the burgeoning scene of the Surrealist and Cubist movements. Groundbreaking young artists such as Balthus, Pablo Picasso and Joan Miro were at the helm of developing radically new techniques in sculpture and painting.

Giacometti's plaster sculpture were based on his close friendship with Andre Breton and the study of his essays on the nature of the unconscious and dreams. This led Giacometti to gradually abandon traditional figurative sculptural techniques, and rely exclusively on visions produced by his imagination as a basis for his subsequent works. In the first stage of this developmental period, his main focus was on the human anatomy, heads, arms and legs, limbs. With "Woman With Her Throat Cut" (1932), Giacometti explored themes of death and madness, against the background of the growing political tensions that were looming large over European nation states in the 1930's. A couple of years later "Hands Holding the Void and Imaginary Objects" (1934) evokes the connection between the sensory experiences of sight and touch. With this piece, Giacometti is trying to explore the extent to which objects conceived in our imagination may also become identical to physical sensations.

At the outbreak of World War II, Giacometti decided to return to Switzerland where he met Annette Arm, a young secretary who became his favourite life-long model. The couple immediately fell in love and married shortly after the end of the War in 1949. This period marks a crucial transition in Giacometti's work as he embarked on a process of producing ever so smaller pieces: both his paintings and sculptures simply started shrinking, a procedure which he claimed he had no control over, but felt irresistibly compelled to pursue.

Shortly after his return to Paris in 1945, Giacometti had an epiphany during which he realised that his work, up to that point had merely been of a cinematographic nature. He was seized by a vision which revealed the physical world around him to be "detachable from time and space." He felt overcome by a sentiment of dread, at the thought that he had, up to that point, deeply misinterpreted the true nature of reality.

This newly found impulse to separate time from his sensory experiences, was a complete revelation, which opened up a new plane of stillness and immobility in his work. He was now able to set the sculptural essence of an object free from his observations, and from their actual presence. This breakthrough allowed him to reverse the drift towards smaller figures he had embarked on during his residency in Switzerland, and to start building bigger models again.

As it turned out, this spurt in vertical growth set him on a course towards designing thinner productions, elongated, spiky sculptures which were instrumental in contributing to Giacometti's growing notoriety and fame in the art world. Although he carried on living modestly, he formed lifelong friendships with the most creative thinkers and artists living in Paris at the time: Pablo Picasso, Samuel Beckett, Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir became regular visitors to his studio and they would routinely socialise together.

In those years which followed World War II, the Existentialists and the Modernists had become very active and increasingly influential with the production of their new idioms and philosophical concepts. Giacometti wanted to take part in defining a new sculptural approach for a new era. His works wrestled with a post war world filled with anguish and uncertainty. He used these unique sculptures to openly reveal the torturous nature of the conflict inherent in trying to create collective meaning after the horrors of the War. He created a multi-figural sense of location and dislocation to apprehend the social ambiguity he and his contemporaries, now lived in. During the decades that had preceded the War, Giacometti had proven himself to be a skilful craftsman, albeit one within the mould of the Cubist and Surrealist traditions.

From the 1960s onwards, he was able to create a completely original visual lexicon, by concentrating his gaze on the interaction between the modelling object, and the space within which it exists. Sartre once famously said that Giocometti's works "always oscillated between nothingness and being." This is confirmed by the fact that Giacometti notoriously incessantly reworked on the same patterns for his sculptures, in an obsessive attempt to capture the fleeting visions which continually occupied his mind. Proportions and distance are constantly flowing either from one another, or to the other, in his figures, and looking at them up close, can sometimes give us the impression that we are looking at an object 100 feet away. The constant thematic thread in Giacometti's art, is that he always comes back to a space where he combines both community and isolation. He extracts them from the atmosphere of a city where a walking man or a female nude character, his favourite models, become the genesis of multiple series, stellar works made out of ashes, and disintegrating structures. Endless repetitions of plaster models, varying in size and range, form a continuum, from delicate naturalism, to quite detailed abstractions.

When faced with it, we cannot help but feel what Giacometti himself said about his work: "Art is only a means of seeing. No matter what I look at, it all surprises and eludes me."

By Andrew Bay, UK

In the late 1950s, Alberto Giacometti's studio in Paris was a safe heaven for some of the most important artists and writers of the 20th century. Jean Genet, the great novelist and playwright once said: "Giacometti's studio was a magic cauldron out of which he could conjure prodigious art, from a messy dump." Plaster mixed with paint and all sorts of scattered materials, filled the sculptor's apartment's floor, feeding his frenzy of creative outbursts. This chaos would eventually find its way onto a frame which would take a permanent form, great art inevitably grown from scraps and debris.

Giacometti was born in Switzerland in 1901, the son of a well established painter. He developed an interest in sculpture from an early age, and decided to become a painter when he was 14 years old. He enrolled at the Geneva School of Fine Arts as a teenager and eventually relocated to Paris in 1923, to study under Emile Bordelles, a former protege of the great sculptor Auguste Rodin.

In Paris, Giacometti rapidly found himself drawn to the burgeoning scene of the Surrealist and Cubist movements. Groundbreaking young artists such as Balthus, Pablo Picasso and Joan Miro were at the helm of developing radically new techniques in sculpture and painting.

Giacometti's plaster sculpture were based on his close friendship with Andre Breton and the study of his essays on the nature of the unconscious and dreams. This led Giacometti to gradually abandon traditional figurative sculptural techniques, and rely exclusively on visions produced by his imagination as a basis for his subsequent works. In the first stage of this developmental period, his main focus was on the human anatomy, heads, arms and legs, limbs. With "Woman With Her Throat Cut" (1932), Giacometti explored themes of death and madness, against the background of the growing political tensions that were looming large over European nation states in the 1930's. A couple of years later "Hands Holding the Void and Imaginary Objects" (1934) evokes the connection between the sensory experiences of sight and touch. With this piece, Giacometti is trying to explore the extent to which objects conceived in our imagination may also become identical to physical sensations.

At the outbreak of World War II, Giacometti decided to return to Switzerland where he met Annette Arm, a young secretary who became his favourite life-long model. The couple immediately fell in love and married shortly after the end of the War in 1949. This period marks a crucial transition in Giacometti's work as he embarked on a process of producing ever so smaller pieces: both his paintings and sculptures simply started shrinking, a procedure which he claimed he had no control over, but felt irresistibly compelled to pursue.

Shortly after his return to Paris in 1945, Giacometti had an epiphany during which he realised that his work, up to that point had merely been of a cinematographic nature. He was seized by a vision which revealed the physical world around him to be "detachable from time and space." He felt overcome by a sentiment of dread, at the thought that he had, up to that point, deeply misinterpreted the true nature of reality.

This newly found impulse to separate time from his sensory experiences, was a complete revelation, which opened up a new plane of stillness and immobility in his work. He was now able to set the sculptural essence of an object free from his observations, and from their actual presence. This breakthrough allowed him to reverse the drift towards smaller figures he had embarked on during his residency in Switzerland, and to start building bigger models again.

As it turned out, this spurt in vertical growth set him on a course towards designing thinner productions, elongated, spiky sculptures which were instrumental in contributing to Giacometti's growing notoriety and fame in the art world. Although he carried on living modestly, he formed lifelong friendships with the most creative thinkers and artists living in Paris at the time: Pablo Picasso, Samuel Beckett, Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir became regular visitors to his studio and they would routinely socialise together.

In those years which followed World War II, the Existentialists and the Modernists had become very active and increasingly influential with the production of their new idioms and philosophical concepts. Giacometti wanted to take part in defining a new sculptural approach for a new era. His works wrestled with a post war world filled with anguish and uncertainty. He used these unique sculptures to openly reveal the torturous nature of the conflict inherent in trying to create collective meaning after the horrors of the War. He created a multi-figural sense of location and dislocation to apprehend the social ambiguity he and his contemporaries, now lived in. During the decades that had preceded the War, Giacometti had proven himself to be a skilful craftsman, albeit one within the mould of the Cubist and Surrealist traditions.

From the 1960s onwards, he was able to create a completely original visual lexicon, by concentrating his gaze on the interaction between the modelling object, and the space within which it exists. Sartre once famously said that Giocometti's works "always oscillated between nothingness and being." This is confirmed by the fact that Giacometti notoriously incessantly reworked on the same patterns for his sculptures, in an obsessive attempt to capture the fleeting visions which continually occupied his mind. Proportions and distance are constantly flowing either from one another, or to the other, in his figures, and looking at them up close, can sometimes give us the impression that we are looking at an object 100 feet away. The constant thematic thread in Giacometti's art, is that he always comes back to a space where he combines both community and isolation. He extracts them from the atmosphere of a city where a walking man or a female nude character, his favourite models, become the genesis of multiple series, stellar works made out of ashes, and disintegrating structures. Endless repetitions of plaster models, varying in size and range, form a continuum, from delicate naturalism, to quite detailed abstractions.

When faced with it, we cannot help but feel what Giacometti himself said about his work: "Art is only a means of seeing. No matter what I look at, it all surprises and eludes me."